Django and WebSocket

Intro

Recently at work I had to think about how we could implement in-app notifications for a single page app. This led me to look into the WebSocket protocol and how to use it with Django applications.

This post is a summary of what I learnt.

Use case

If you have a webpage where you want information to be updated automatically, without having to refresh the page, there are a few options available:

-

Short polling: the client makes a request to the server every couple of seconds to check if there is an update. This has the following disadvantages:

- It creates a lot of traffic to the server

- Depending on how long the interval is between the requests, there can be a delay between when the data changes and when it is updated on the webpage.

-

Long polling: the client makes a request to the server and the server keeps this connection open until it has data to communicate back to the client. Once the server responds, the connection is closed. This has the following disadvantages:

- There is the overhead of opening a new connection for every data exchange [1].

- It can be resource intensive, since while the server is waiting to return data it is essentially “hanging”.

-

WebSocket: a 2-way persistent connection is opened between the client and the server. The server can send data to the client without needing a request first. This has the advantage of achieving real time updates while using less resources, but it has the following disadvantages:

- A more complex setup is needed.

- Old browsers don’t support WebSocket.

WebSocket

WebSocket is a communication protocol. It provides a 2-way simultaneous communication channel over a single TCP connection.

It is different from HTTP, but it was designed to work over HTTP ports 443 and 80 and it supports going through HTTP proxies and intermediaries. This means that it is compatible with HTTP: to start a WebSocket connection you make an HTTP request with the HTTP Upgrade header. [2]

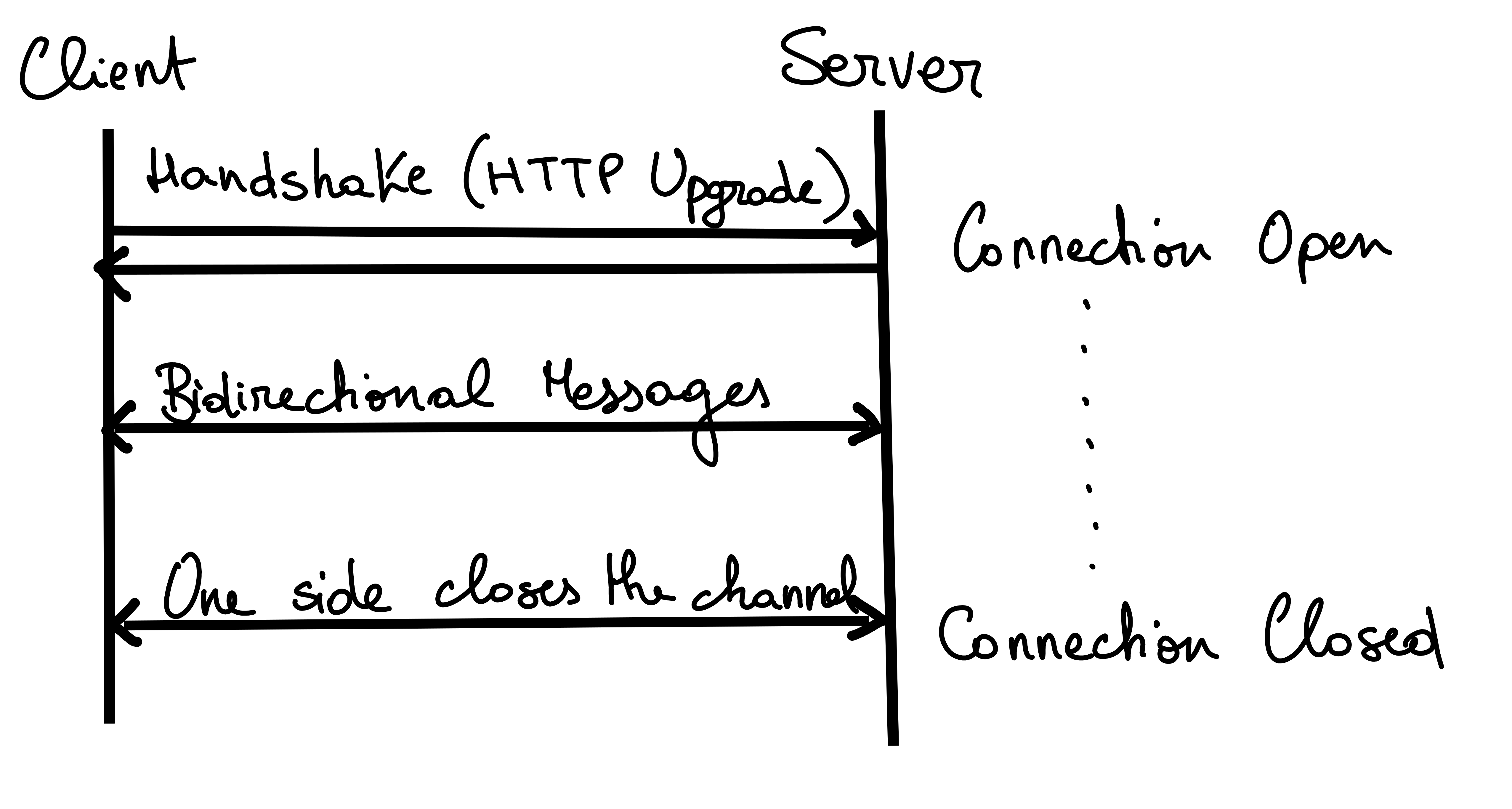

The image below shows the process of opening a WebSocket connection between a client and a server.

While the connection is open, both the client and the server can send messages to each other.

Django and WebSocket

WSGI vs ASGI

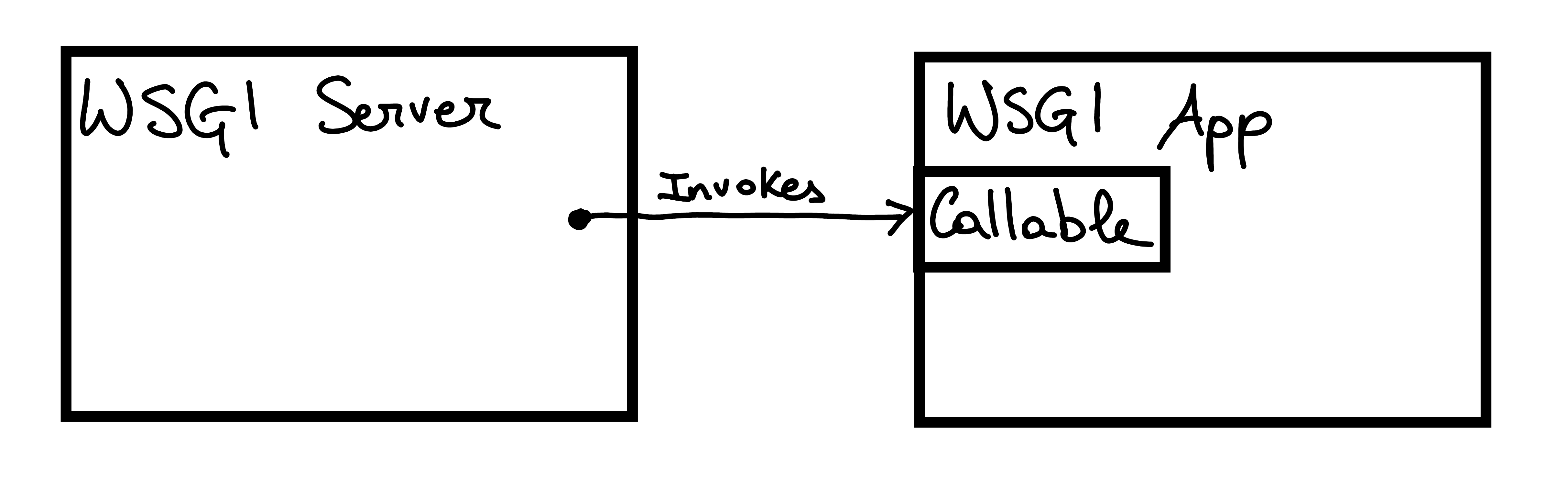

Web Server Gateway Inteface (WSGI) is the standard for running Python web applications. [3]

The WSGI standard defines the interface between the web server and the web application. So it has two sides: the “server” side and the “application” side. [4] The server side receives requests from the “outside world” and invokes a synchronous callable object that is provided by the application side. The application takes information about the received request and produces a response. The response is then forwarded back by the server.

Here is a minimal “Hello world” WSGI application [5]:

def application(environ, start_response):

start_response('200 OK', [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')])

yield b'Hello, World!\n'

When a WSGI server receives a request, it invokes this application which then returns a response with status code 200 and the plain text “Hello, World!”.

The WSGI standard is not suitable for long lived connections like WebSocket.

For this reason, the Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface (ASGI) standard was introduced. ASGI is a superset of WSGI designed to support forwarding requests to asynchronous capable Python applications. [6]

An ASGI compatible application is an asynchronous program that takes a “scope” (details about the connection), a callable to send messages and a callable to receive messages.

This is an example of an ASGI application [7]:

async def application(scope, receive, send):

event = await receive()

await send({"type": "websocket.send", "text": "Hello world!"})

The two main differences with the WSGI application are the fact that it is an asynchronous function and that it also has a callable to receive messages.

Django Channels

Django applications are WSGI compatible, but not ASGI compatible. Therefore, the Django Channels project was started. [8] Django Channels aims to make Django ASGI compatible so that, among other things, it can handle WebSocket connections. It was designed to be compatible with “normal” Django in order to keep WSGI applications working.

Django works by taking an incoming request and routing it down to the right View which handles the request and produces a response.

Django Channels works around the concept of events. When an event happens, a message is put into a queue. Consumers listen for these messages and can execute some code and/or send additional messages.

In order to understand how Django Channels works, it is useful to understand the following terms that are used in the documentation.

Channels

The channel is an “ordered, first-in first-out queue with message expiry and at-most-once delivery to only one listener at a time”. [9].

Whenever a client opens a WebSocket connection, a channel with a unique name is created.

Consumers

Consumers listen for messages that are loaded on particular channels. Whenever a message is received, they can run some code or send additional messages. They can also send messages back to the client over an open WebSocket connection.

Each consumer is associated with a unique channel name that can be used to communicate with a specific client, since each consumer will live until the connection is closed. When the consumer is instantiated, it receives a scope (information about the connection), a callable to send messages and a callable to receive messages. [10]

Channel groups

When there are multiple instances of the same consumer at the same time, it must be possible to send messages to all the associated channels. For this, there is the concept of a “channel group”. You can write your consumers so that whenever a connection is opened, the unique channel name is added to a group. Then, whenever an event happens, a messages can be sent to all the channels that are in that group.

This is useful for example in the following scenaro. Think of a chat application, where many clients are connected to a server. If a user sends a new chat message, you want to communicate it to all the connected clients. This can be done by using a “channel group”. The consumer will load a message in all the channels in a group which will then be forwarded to all the connected clients.

Producers

Any code that loads messages into a channel.

Channel layer

Python code that handles loading messages into a queue and receiving messages from it. Can be seen as a wrapper of the “Channels backend”.

For example, when using the RedisChannelLayer, this layer receives the messages and handles sending/retrieving them to/from the Redis backend [11].

Deploying Django Channels applications

There are more than one way to deploy Deploying Django Channels applications. Some options:

- Exactly like “normal” Django apps. If no channel layer is specified, Django Channels apps work just like WSGI apps. However, they will only support HTTP traffic.

- Only with an ASGI server. All traffic, including HTTP traffic, goes through the ASGI server.

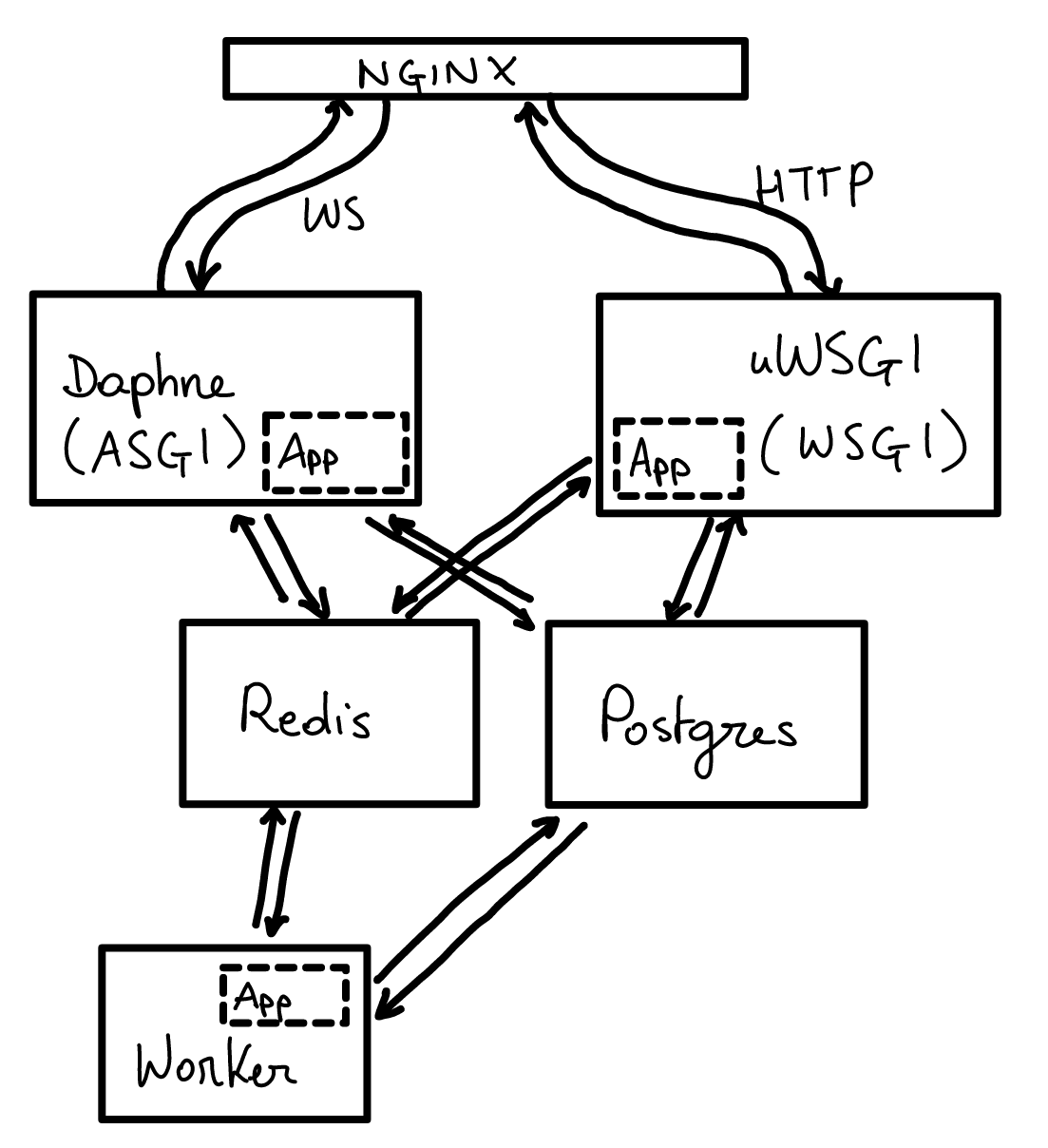

- With both an ASGI and a WSGI server. In this case, the WSGI server can handle the HTTP traffic, while WSGI server handles the WebSocket and/or HTTP/2 traffic.

According to the documentation, it may be preferable to route HTTP traffic to a WSGI web server while routing all WebSocket and HTTP/2 to the ASGI server. This is because the ASGI specification and Daphne are relatively new, so they are still less “battle tested” [12].

For options 2. and 3., a few components are needed. In the Django Channels documentation, they mention [13]:

- An “interface” server

- A channel backend

- Worker servers

Interface servers

The interface server is a web server. It has the role of receiving incoming requests and loading messages into the channels.

A common choice of ASGI interface server is Daphne [14].

It is important to run the interface server inside some program that can take care of restarting the process when it exits for whatever reason.

When running both an ASGI and WSGI server, a reverse proxy (like nginx) needs to be added. It takes incoming requests and routes the HTTP traffic to the WSGI server and other traffic to the ASGI server.

Channels backend

One has to choose a backend supported by one of the Channel Layers [15]. The recommended backend is Redis.

Workers

These are mini-ASGI compatible applications that talk to the Channels backend. They listen on either specified channels or all channels and can perform some work, including spinning up consumers to handle requests. The work of running consumers is decoupled from the work of talking to clients, so you can run multiple “worker servers” to do additional processing of messages.

It is important to also run workers inside some program that can take care of restarting the process when it exits, since the worker itself has no retry-on-exit logic.

Putting it together

Here is a diagram showing which containers could be used to deploy an application with both a WSGI and an ASGI server.

For a toy project putting these concepts together, you can look here.

In this toy project, there is a “counter” model and there is a simple API to retrieve the value of the counter and increment it. Then, there are two pages (simulating a ‘frontend’) one of which displays the value of the counter and one with a button to increment the counter.

The page that displays the counter also opens a WebSocket connection with the backend, so whenever the button is pressed in the other page, the value is updated without needing to refresh.

You see this in action by running the docker compose and going to http://localhost:9000/counter/ and http://localhost:9000/increment/.

Conclusion

In this post we looked at how to make Django applications support the WebSocket protocol using Django Channels.